Shalom Aleichem.

Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.

Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.

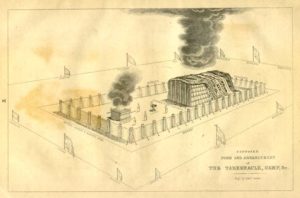

Reflecting again, back to the final readings in Exodus, the Book of Shemot, we read about the construction of the Sanctuary, the Mishkan– and we read about fire. Fire is an element that follows us throughout Torah: God appeared to Moses in a burning bush; the Golden Calf “appeared” to Aaron and the Israelites out of fire; fire was carefully modulated to create the golden Chrubim, Keruvim and other elements of the Mishkan, and now we read about fires consuming sacrifices. In Hebrew the word for sacrifice is korban, plural, korbanot, and implies a coming closer, nearer to God. We are also taught to not make fire on Shabbat and on Festivals. Fire, then, is both a negative and positive element as are our mitzvot, and fire follows us from Shemot into Leviticus, Vayikra, and this week, into Tzav.

Lying awake thinking about fire and the sacrifices in Tzav I knew I must go to the Gerer, the Sefat Emet, and open the pages of his teachings.

He too notes that fire again appears in Tzav. In 6: 1 we read …”a fire must always burn on the altar, it must not go out.” The Sefat Emet teaches us that the fire that must always burn is in fact our own yirah, our own state of awe/fear of God. We learn in Tzav that wood “shall burn upon (the altar) every morning”; now this burning wood represents our love for God within. The Gerer teaches this love is the “thread of grace,” a phrase from Psalm 42:9, “God commands His grace by day, and at night His song is with me.” Flames burn wood, wood burns our korbanot– and flames of those sacrificial korbanot bring us closer to God. Just as we weave our soul-threads into the holy tapestry of Judaism, so we weave that tapestry with threads of chen, of God’s grace.

We read in Tzav we are to remove the ashes of the previous night’s fire every morning. I grew up with a wood stove, a sawdust furnace, and a fireplace. Every morning there were ashes to clean up. Ashes must be swept up quietly and deliberately, otherwise ash floats and shmears well beyond any original containment. Ashes are not waste. Ash is a necessary nutrient, an element that with vegetable and animal remains, compost and manure, returns to earth to enable re-growth. Creation and destruction emerge from the cycles of fire and ash.

The Gerer teaches us that ash, remains of depleted fire, also renews us symbolically each day. We are renewed in love, as a fire of prayer rekindles us anew every morning. A traditional siddur opens the Shacharit service with readings from Tzav. …”a fire must always burn on the altar, it must not go out.” And so what once stood – our Temple, our Beit haMikdash, and what once burned– our korbanot, our sacrifices – are now transformed into prayer, the fire and ash within our souls. We now have a duty every day to rise, and clean ashes from our inner hearths to make room for new fire: Fire and ash, our daily cycle of prayer.

We build fires as protection, proof against darkness, and then, by light greying into dawn, we sweep those ashes and return them to the ground of our being. We live in yirah, that liminal space between fear and awe. We are all agents of construction and destruction. We love in a flame of passion; we also know that love can dissipate into ashes, tasteless in our mouths, mouths that were once open and hungry for burning kisses, can close. But a spark, always a spark, remains.

We speak of that pintele Yid, that small, often almost completely hidden spark within every Jew. “A fire must always burn, it may not go out.” That pintele spark cannot go out, cannot be extinguished, even as it may barely be felt. Our tradition teaches us that any awakening of soul, of ruach might cause that tiny spark to flicker into flame.

Tzav. In a word, we are commanded to recognize our place at the hearth of yirah. Tzav commands our renewal of soul-spark every day. Tzav, truly that commanding unbroken circle of fire and ash.

Aleichem shalom.

Tzav

March 19, 2019 by Rabbi Lynn Greenhough • From the Rabbi's Desk

Shalom Aleichem.

Reflecting again, back to the final readings in Exodus, the Book of Shemot, we read about the construction of the Sanctuary, the Mishkan– and we read about fire. Fire is an element that follows us throughout Torah: God appeared to Moses in a burning bush; the Golden Calf “appeared” to Aaron and the Israelites out of fire; fire was carefully modulated to create the golden Chrubim, Keruvim and other elements of the Mishkan, and now we read about fires consuming sacrifices. In Hebrew the word for sacrifice is korban, plural, korbanot, and implies a coming closer, nearer to God. We are also taught to not make fire on Shabbat and on Festivals. Fire, then, is both a negative and positive element as are our mitzvot, and fire follows us from Shemot into Leviticus, Vayikra, and this week, into Tzav.

Lying awake thinking about fire and the sacrifices in Tzav I knew I must go to the Gerer, the Sefat Emet, and open the pages of his teachings.

He too notes that fire again appears in Tzav. In 6: 1 we read …”a fire must always burn on the altar, it must not go out.” The Sefat Emet teaches us that the fire that must always burn is in fact our own yirah, our own state of awe/fear of God. We learn in Tzav that wood “shall burn upon (the altar) every morning”; now this burning wood represents our love for God within. The Gerer teaches this love is the “thread of grace,” a phrase from Psalm 42:9, “God commands His grace by day, and at night His song is with me.” Flames burn wood, wood burns our korbanot– and flames of those sacrificial korbanot bring us closer to God. Just as we weave our soul-threads into the holy tapestry of Judaism, so we weave that tapestry with threads of chen, of God’s grace.

We read in Tzav we are to remove the ashes of the previous night’s fire every morning. I grew up with a wood stove, a sawdust furnace, and a fireplace. Every morning there were ashes to clean up. Ashes must be swept up quietly and deliberately, otherwise ash floats and shmears well beyond any original containment. Ashes are not waste. Ash is a necessary nutrient, an element that with vegetable and animal remains, compost and manure, returns to earth to enable re-growth. Creation and destruction emerge from the cycles of fire and ash.

The Gerer teaches us that ash, remains of depleted fire, also renews us symbolically each day. We are renewed in love, as a fire of prayer rekindles us anew every morning. A traditional siddur opens the Shacharit service with readings from Tzav. …”a fire must always burn on the altar, it must not go out.” And so what once stood – our Temple, our Beit haMikdash, and what once burned– our korbanot, our sacrifices – are now transformed into prayer, the fire and ash within our souls. We now have a duty every day to rise, and clean ashes from our inner hearths to make room for new fire: Fire and ash, our daily cycle of prayer.

We build fires as protection, proof against darkness, and then, by light greying into dawn, we sweep those ashes and return them to the ground of our being. We live in yirah, that liminal space between fear and awe. We are all agents of construction and destruction. We love in a flame of passion; we also know that love can dissipate into ashes, tasteless in our mouths, mouths that were once open and hungry for burning kisses, can close. But a spark, always a spark, remains.

We speak of that pintele Yid, that small, often almost completely hidden spark within every Jew. “A fire must always burn, it may not go out.” That pintele spark cannot go out, cannot be extinguished, even as it may barely be felt. Our tradition teaches us that any awakening of soul, of ruach might cause that tiny spark to flicker into flame.

Tzav. In a word, we are commanded to recognize our place at the hearth of yirah. Tzav commands our renewal of soul-spark every day. Tzav, truly that commanding unbroken circle of fire and ash.

Aleichem shalom.