Shalom Aleichem.

Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import.

Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import.

Ki Tisa is about our relationships – with each other and with God. One of the primary ingredients necessary in any relationship – as any long-married couple will tell us – is patience. Not just endurance, which implies a certain thin-lipped fortitude, but generous-hearted patience.

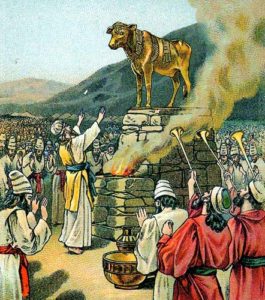

Who holds patience for us? In Ki Tisa we read how God gave Moses a precious gift, two tablets of stone inscribed by the very “finger” of God. But then God noted to Moshe the corruption of the people at the base of the mountain, dancing in front of flames and, heaven forfend, a golden calf. God wanted to annihilate the people, but agreed to reconsider such an action after Moshe’s fervent pleading for God to, “Relent from your flaming anger and reconsider…”

But Moshe’s own anger then flared, and as he descended, he smashed down the two Tablets, desolate and furious as he was with the Israelites. What did God eventually say to Moshe?

We read, “At that time, God said to me, ‘Carve for yourself two stone Tablets like the first ones, and I shall inscribe on the Tablets the words that were on the first Tablets that you shattered.’” Let’s do it again.

God then reveals God’s Self in 13 attributes of Compassion, Kindness and Truth – (perhaps ironically) Slow to Anger, and more. Attributes that are actions. Kindness is a verb. Patience is a verb.

And so Moshe and God worked together again, to carve and inscribe. Just do it – again. And thus we learn that every day we must carve out the words that will become the ground of our relationships. And always, behind those words, those second chances, we need patience.

In Ki Tisa, even though the impatient people of k’lal Yisroel have provoked Moshe into a fury, and God is ready to annihilate them, both Moshe and God, in turn, restrain the other, and ultimately, we are given the benefit of their doubt.

This past week I read a note from a friend, regarding a book he was reading, “The Order of Time” by Carlo Rovelli. Rovelli pointed out that Descartes *first* principle is “Dubito ergo cogito.” “I doubt therefore I think”. My friend noted a teaching from Rabbi Sharon Brous about the first foundational questions asked of humans in Torah—where are you, and where is Abel your brother? What is an individual and what is an individual in relation to others?

Then Rabbi Waskow stepped into the conversation (he and my friend are machatonim). R. Waskow noted that a former colleague of his, (Marc Raskin, alavhashalom), used to say, contra Descartes, “I feel, therefore I am.” And then Rabbi Waskow brought in another teaching from Reb Zalman, alav hashalom.

Perhaps to truly, “am”, one has to be, think (including “doubt”), feel, act. So, to continue the thought, Reb Zalman then asked, “Why is there a Yomtov sheni, a 2nd day of the Festivals? Because of doubt about which is the correct date. Should we keep celebrating the 2nd day even though our astronomers can now calculate the Renewal of the Moon to the precise second? Yes, because there should be a Yontif for doubt as well as a Yontif for faith.

Love is patient. Love is about always saying I’m sorry. Love is never perfect and it will never be enough. In our relationships with each other and with God, we need to set our patience meter higher than we ever imagined. We need to hold that patience we call faith. And we need a measure of doubt.

Aleichem shalom.

Ki Tisa

February 19, 2019 by Rabbi Lynn Greenhough • From the Rabbi's Desk

Shalom Aleichem.

Ki Tisa is about our relationships – with each other and with God. One of the primary ingredients necessary in any relationship – as any long-married couple will tell us – is patience. Not just endurance, which implies a certain thin-lipped fortitude, but generous-hearted patience.

Who holds patience for us? In Ki Tisa we read how God gave Moses a precious gift, two tablets of stone inscribed by the very “finger” of God. But then God noted to Moshe the corruption of the people at the base of the mountain, dancing in front of flames and, heaven forfend, a golden calf. God wanted to annihilate the people, but agreed to reconsider such an action after Moshe’s fervent pleading for God to, “Relent from your flaming anger and reconsider…”

But Moshe’s own anger then flared, and as he descended, he smashed down the two Tablets, desolate and furious as he was with the Israelites. What did God eventually say to Moshe?

We read, “At that time, God said to me, ‘Carve for yourself two stone Tablets like the first ones, and I shall inscribe on the Tablets the words that were on the first Tablets that you shattered.’” Let’s do it again.

God then reveals God’s Self in 13 attributes of Compassion, Kindness and Truth – (perhaps ironically) Slow to Anger, and more. Attributes that are actions. Kindness is a verb. Patience is a verb.

And so Moshe and God worked together again, to carve and inscribe. Just do it – again. And thus we learn that every day we must carve out the words that will become the ground of our relationships. And always, behind those words, those second chances, we need patience.

In Ki Tisa, even though the impatient people of k’lal Yisroel have provoked Moshe into a fury, and God is ready to annihilate them, both Moshe and God, in turn, restrain the other, and ultimately, we are given the benefit of their doubt.

This past week I read a note from a friend, regarding a book he was reading, “The Order of Time” by Carlo Rovelli. Rovelli pointed out that Descartes *first* principle is “Dubito ergo cogito.” “I doubt therefore I think”. My friend noted a teaching from Rabbi Sharon Brous about the first foundational questions asked of humans in Torah—where are you, and where is Abel your brother? What is an individual and what is an individual in relation to others?

Then Rabbi Waskow stepped into the conversation (he and my friend are machatonim). R. Waskow noted that a former colleague of his, (Marc Raskin, alavhashalom), used to say, contra Descartes, “I feel, therefore I am.” And then Rabbi Waskow brought in another teaching from Reb Zalman, alav hashalom.

Perhaps to truly, “am”, one has to be, think (including “doubt”), feel, act. So, to continue the thought, Reb Zalman then asked, “Why is there a Yomtov sheni, a 2nd day of the Festivals? Because of doubt about which is the correct date. Should we keep celebrating the 2nd day even though our astronomers can now calculate the Renewal of the Moon to the precise second? Yes, because there should be a Yontif for doubt as well as a Yontif for faith.

Love is patient. Love is about always saying I’m sorry. Love is never perfect and it will never be enough. In our relationships with each other and with God, we need to set our patience meter higher than we ever imagined. We need to hold that patience we call faith. And we need a measure of doubt.

Aleichem shalom.