Tzav

Shalom Aleichem.

Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.

Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.

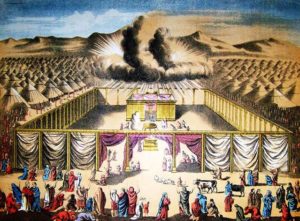

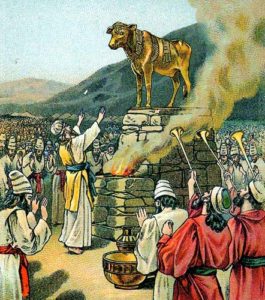

Reflecting again, back to the final readings in Exodus, the Book of Shemot, we read about the construction of the Sanctuary, the Mishkan– and we read about fire. Fire is an element that follows us throughout Torah: God appeared to Moses in a burning bush; the Golden Calf “appeared” to Aaron and the Israelites out of fire; fire was carefully modulated to create the golden Chrubim, Keruvim and other elements of the Mishkan, and now we read about fires consuming sacrifices. In Hebrew the word for sacrifice is korban, plural, korbanot, and implies a coming closer, nearer to God. We are also taught to not make fire on Shabbat and on Festivals. Fire, then, is both a negative and positive element as are our mitzvot, and fire follows us from Shemot into Leviticus, Vayikra, and this week, into Tzav.

Many of our teachings in Torah were and are revolutionary – in every way from economic to social. In the book of Exodus, of Shemot we were called to remember and keep Shabbat. Let’s try and think for a few minutes about how utterly revolutionary that command was and still is: Stop working. Do not engage in any manner of creative work.

Many of our teachings in Torah were and are revolutionary – in every way from economic to social. In the book of Exodus, of Shemot we were called to remember and keep Shabbat. Let’s try and think for a few minutes about how utterly revolutionary that command was and still is: Stop working. Do not engage in any manner of creative work. We open up Pekudei and read:

We open up Pekudei and read:  In this week’s Torah portion, we again meet Bezalel, the Leonardo da Vinci of the Mishkan world. We learn in Exodus 35:30-34:

In this week’s Torah portion, we again meet Bezalel, the Leonardo da Vinci of the Mishkan world. We learn in Exodus 35:30-34: Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import.

Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import. I alluded last week to my maniacal preparations for my own ceremony of Bat Mitzvah as a grown woman, and as someone who chose to enter the covenant. Mishpatim is that sidra that caused me to pause and consider my need to allow others to help me prepare for that day.

I alluded last week to my maniacal preparations for my own ceremony of Bat Mitzvah as a grown woman, and as someone who chose to enter the covenant. Mishpatim is that sidra that caused me to pause and consider my need to allow others to help me prepare for that day. Yitro is the חוֹתֵן, the father-in-law of Moshe, a relationship that is reiterated and reinforced many times in the first section of this sidra. The name Yitro means abundance or riches – and truly this is what Yitro gave to Moshe. Not riches of kind, but of counsel regarding sustainability, practical counsel that would yield abundance for generations to come.

Yitro is the חוֹתֵן, the father-in-law of Moshe, a relationship that is reiterated and reinforced many times in the first section of this sidra. The name Yitro means abundance or riches – and truly this is what Yitro gave to Moshe. Not riches of kind, but of counsel regarding sustainability, practical counsel that would yield abundance for generations to come.

Shemini

March 27, 2019 by Rabbi Lynn Greenhough • From the Rabbi's Desk

Sung in Eichah trop

“Aaron was silent” (Lev. 10:3).

My sons. I cannot breathe, I cannot speak their names, my heart has no words, just No, I say no, this cannot be; when all that is left of my boys is ashes.

Their names folded into that fire- air, flames that sucked breath from their souls.

God, you chose me, You dressed me, you have me set aside portions of korbanot to taste, yet all I taste today is ashes. You chose me – and through me You chose my sons – for this, for this, you chose me?

More