Selling Chametz – Information and Form

With thanks to Rabbi Sutker and Rabbi Blane

Why sell?

Divesting ourselves of chametz, the old food in our pantries, is one of the important rituals of preparing for Pesach/Passover. On the physical level, this ritual offers us an opportunity to clean out our kitchens. Perhaps more importantly, while doing the physical work of cleaning, we have the opportunity for a spiritual assessment. Such work offers us an opportunity for self-examination. We can ask ourselves what old habits we have been clinging to, and how we want to nourish ourselves spiritually in the future.

Tzaraas. Afflictions, in more pustular detail than you had ever imagined!

Tzaraas. Afflictions, in more pustular detail than you had ever imagined!  Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.

Tzav – command! The word is a sticky, fricative syllable that in one iteration or another crosses our lips daily as we perform a mitzvah.  Many of our teachings in Torah were and are revolutionary – in every way from economic to social. In the book of Exodus, of Shemot we were called to remember and keep Shabbat. Let’s try and think for a few minutes about how utterly revolutionary that command was and still is: Stop working. Do not engage in any manner of creative work.

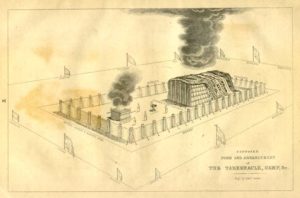

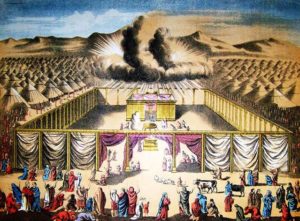

Many of our teachings in Torah were and are revolutionary – in every way from economic to social. In the book of Exodus, of Shemot we were called to remember and keep Shabbat. Let’s try and think for a few minutes about how utterly revolutionary that command was and still is: Stop working. Do not engage in any manner of creative work. We open up Pekudei and read:

We open up Pekudei and read:  In this week’s Torah portion, we again meet Bezalel, the Leonardo da Vinci of the Mishkan world. We learn in Exodus 35:30-34:

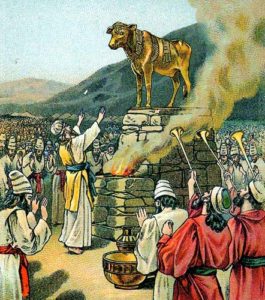

In this week’s Torah portion, we again meet Bezalel, the Leonardo da Vinci of the Mishkan world. We learn in Exodus 35:30-34: Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import.

Life has many blessings, and many pitfalls. So too does Ki Tisa. This is another one of those parshiot filled with verbs – remember, provoked, ascended, descended, smashing, carved – as if to remind us that every action we take, even the act of intention, holds tremendous import.

Pesach

April 17, 2019 by Rabbi Lynn Greenhough • From the Rabbi's Desk Tags: notre dame, pesach, seder •

Chag sameach everyone, I hope you all have a freilech, a joyous Seder and Pesach.

Even as some of us may be scrubbing corners of cupboards and thinking about menus for the coming week, I have suggested that this is also a time for us to take a spiritual inventory, an opportunity for cleaning out the inner shmutz that may have collected over this past year.

More